Escape Artists

At a time when we’re all eager for an imaginative respite, three artists offer a creative escape rooted in their unique brands of fantasyThis past year, many of us have been forced to rediscover a world of boredom that we haven’t know since we were kids. The challenges have been many, and yet, our imaginative child-minds have returned as well, opening the door to fantasy worlds as we dream of less languid days. Like many artists, Katie Stout, Hanna Hedman, and Zach Harris have been operating in this space since long before the pandemic, creating work that stems from their imagination. What makes their art unique is their ability to take things to the next level—creating pieces whose hallmark is pure, unadulterated, all-encompassing fantasy. We spoke with them about how their individual brand of creativity and imagination informs their practices, and why it may be more important now than ever.

Katie Stout

Katie Stout has often had those moments where she’s with a friend, and the friend waves their hand in front of her face, maybe snaps their fingers.

“They’re like, ‘Uh, where’d you go?’” she says over the phone from her studio in New York. But it’s those daydreams that are the seeds from which her work grows. “That’s when it all happens—in that zone-out, not-here moment,” she says. “You’re in this trance.”

A native of New Jersey, Stout is well known in the art and design world, creating what could be furniture for the cool teenagers of a neighboring dimension. Her pastel installations and hypercolor ceramic lamps often depict women—she calls them her “lady lamps” with a giggle—but are formed in the shapes of fruits and vegetables. Lately she’s been making them slightly rotten, little ceramic flies dotting their bodies.

She’ll be showing these works at the Venus Over Manhattan gallery in New York from April 6 to May 1, and she credits her imagination for allowing her to process certain experiences she’s had into vibrant, beautiful objects.

“One of the reasons why I’ve been creating the things I do is that it has been a tool for me to process bad things that have happened,” she says. “It allows me to see things in a different way, and I want other people to see them in that way, where we get to create our own worlds, and they can be as fantastical as we want them to be.”

And now, more than ever, Stout argues, fantasy is critical.

“It allows you to think of a world that you want to live in,” she says. “And I think that’s something we’re all thinking about right now. It would be really bad if people stifled themselves and didn’t allow themselves to fantasize. I’m not a scientist, but it has to be healthy for you.”

Hanna Hedman

Hanna Hedman has always found her inspiration in the outdoors. It’s fitting then that many of her works exist in public spaces—eight of her pieces are public artworks around Sweden, with another three coming in 2021. Even her furniture and jewelry design—such as her Becoming Nature furniture series—is full of natural forms. You may be able to sit on her chairs and eat at her tables, but they will always remind you that leaves and seaweed are near.

“I grew up around nature and have a strong relationship with nature,” Hedman explains from Stockholm. “I have spent many hours by myself in the forest running or skiing.”

The patterns and forms of the wilderness spark something inside her, as implicated in her work. But, for Hedman, it is something more, something ineffable.

“The primal chaos of nature is very inspiring—those aspects of human experience, and those beyond language as well,” she says.

It’s these experiences that manifest themselves into forms forged in steel—Hedman’s primary medium. Despite the hardness of the material, Hedman’s works offer a gentle malleability, welcoming the viewer.

“I create my artwork to be an entrance, offering a sense of escape into a mysterious and indefinable world that continues to tell stories beyond what we see in the objects,” she says. “I often work in series, where a larger group of objects is presented at the same time with the intention of entering into another world or atmosphere.”

In this, Hedman feels a sense of the fantastical that is intrinsic to her work. Fantasy, she says, is something to cherish.

“We all have the magical ability to use fantasy to create new worlds, both actual physical and fictional, and make them real,” she explains, noting that life with her two children, ages 2 and 5, means her days are filled with elements of pretend.

“It’s very important to both younger and older [people], and something to take seriously,” she says. “I don’t see it as escapism, but rather a tool that we can use. We are looking at a future where we will have many challenges that we need to learn to live with. Climate change will require new ways of living, traveling, new systems, and new science. Fantasy can help us change our behaviors.”

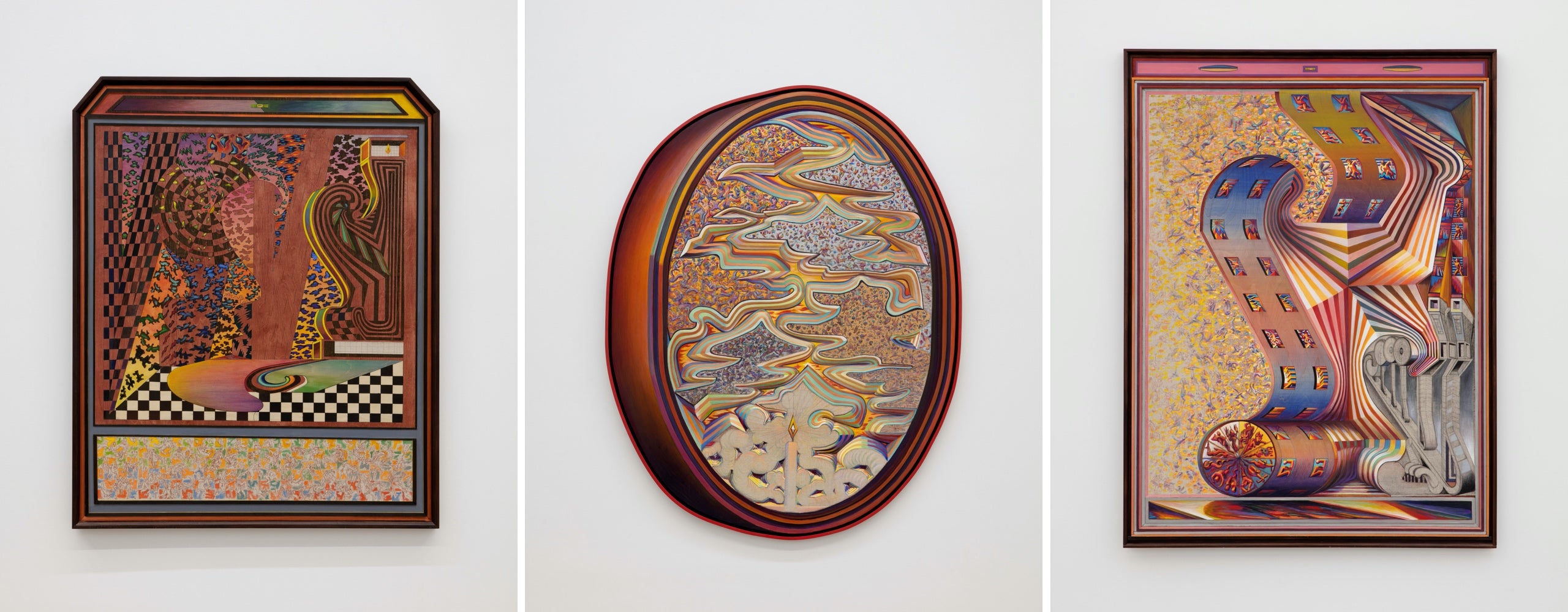

Zach Harris

Hearing Zach Harris describe his paintings is one of the best ways to experience them. His vivid narratives range from how one painting is like a filmstrip to how a figure on the canvas is going through the evolution from a creature evolving into a human and then into an alien and then into a planet. In another painting, he describes, he has designed a harp that becomes a bird. That bird flies up and becomes a sky, and in that sky are people that make up the bird.

“They’re surreal narratives,” he says on a phone call while driving through Los Angeles, where he lives, “as much as an image can be a narrative.”

Harris taps deeply into his subconscious, letting ideas fester and float around in his mind for years—literally meditating on them—before allowing them to come out as he does drawings in preparation for his paintings. The results are intricate, larger-than-life canvases (sometimes 9 feet in height) that pop with a heavy dose of psychedelic color and a twisty, near-soothsaying vision of these interesting times.

“In 2016, after the election, I started thinking a lot about 2020, and the numerology of it and the election, and I was like, ‘2020 is going to be a crazy year,’” he says, describing a series of surrealist calendars and clocks and zodiac paintings. “I had this apocalyptic vision. I do a lot of drawing on linen these days—it’s stream of consciousness stuff. I was projecting this year was going to be intense, which it turned out to be, and way more than that.”

The paintings for his show at Perrotin gallery in New York from March 4 through April 17 reflect that intensity—there’s a certain Boschian nature to them, hundreds of characters writhing around on the canvas. But there’s something comforting in spending time looking at the work, following the action—even Harris calls his paintings “escapist.” After all, that’s his intention, to create a work that sucks the viewer in.

“I love deep landscape space—a space in a painting that’s very illusionistic that you can travel into,” he says. “Once I make this world you can go into, it becomes fantastical. You can just invent crazy mountain ranges with lights coming out of the tops of the mountains. That’s the bigger metaphysical quality of the work—I’m tripping out on these spaces, and inviting the viewer to come along on the ride.”

- Images courtesy of Katie Stout

- Images courtesy of Hanna Hedman

- Images courtesy of Zach Harris