Once Upon a Time in the West

How a generation of artists and museums are blazing a new trail of American cowboy artConsider the cowboy. Actually, reconsider the cowboy. That’s what a new generation of artists and museums are doing. They are retelling the story of the all-American icon in a new light. Not content to continue on the path of their elders—yet not so irreverent as to ignore the legacy of work that precedes them—these creative minds are redefining the cowboy with an image that better fits the complex historic reality of the West.

Though these painters come from a range of backgrounds, their destination is often the same. Their work hangs alongside pieces by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, among other Old Masters of the form, in revered locales like the Museum of Western Art in Kerrville, Texas; the Black Cowboy Museum in Rosenberg, Texas, near Houston; the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio; and the Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles.

Some draw their details from lived experiences working ranches across the West; one is a former music video director from France. Taken together, their work amounts to a large-scale renaissance, and critique, of one of the country’s most distinct artforms, one that feels both out of time and of the moment.

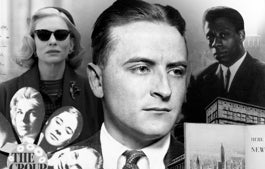

Take Teal Coke Blake, for example. He grew up “immersed in both worlds,” as he puts it, meaning the art world and the West. He went to college on a rodeo scholarship, raises horses near Fort Worth, and grew up in Montana—where, as the son of a Western artist and a fashion photographer mother, his family’s guests included Richard Avedon. This background comes through in both the whimsy and the authenticity of his work. (He has depicted both horse-riding pinup girls and dead horses rotting in the sun.) He often paints in watercolor on an unusual “canvas”—old ledgers he sources from antique shows and friends. “I had never seen anybody do cowboy art with them,” he says. He began using them six or seven years ago with one he found in Dillon, Montana, for $5 or $6. “I did a little drawing on it, and it just took off. I had everybody wanting them. I was so tickled that everybody likes those so much.”

Blake says his experience with horses feeds into his art, because as a rancher, he can go out and spend a night and see things other people might miss, like the light coming up in the early morning. “I’ve been spoiled,” he says. “I haven’t had to try very hard. As long as I have a memory, I have images that can last me the rest of my life.”

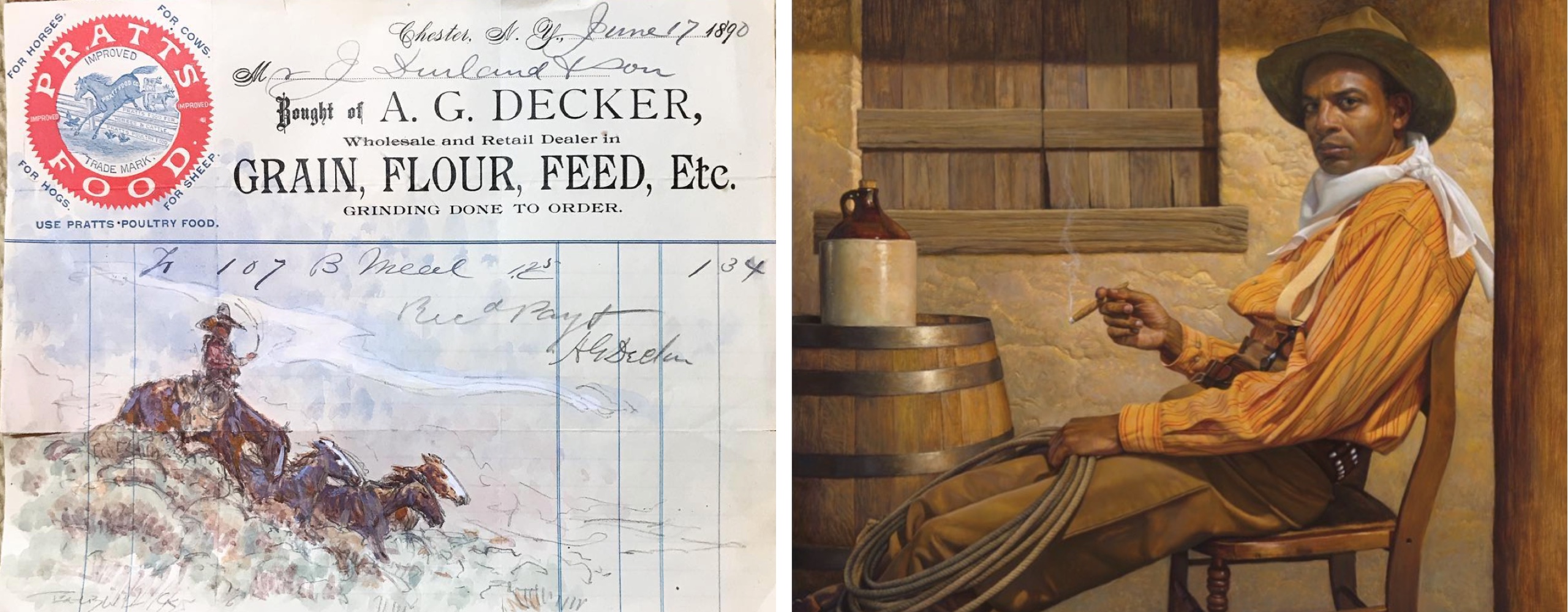

Another artist, Logan Maxwell Hagege, approaches his subjects with humility, using his large-scale canvases to channel “the feelings I have of love for the people in the work,” he says. His pieces are often bold and bright, featuring both cowboys and indigenous people he comes across in the Southwest.

For Mark Maggiori, a French-born filmmaker who gave up his career to move to Taos, New Mexico, it started in childhood, watching Westerns. It took hold from there as he came across the Taos Society of Artists, a widely influential early 20th-century cooperative of painters. “I discovered the art behind it,” he says. “I had no idea because Western art isn’t popular in France. Seeing those paintings, I really liked what they show—nature, which I love; the American West, which I love. Attire, gear, clothing.” By 2014, he had begun refusing all video work to focus on his art, which in turn took off with the help of Instagram. The events of recent years—including the murder of George Floyd and the widespread fight for racial justice—prompted the project, #thewestofmanycolors, in which he depicts Black cowboys. It culminated in “Once Upon a Time,” a painting that now hangs in the Briscoe’s permanent collection.

“I’m very honored,” he says. “This is a way to rectify history, the way it’s been whitewashed by Hollywood. I was part of that, I had no idea about the Black cowboy. It’s not just white guys on horses.” Indeed, roughly one in five cowboys were Black, Indigenous, or what we would now consider Latinx, according to Michael R. Grauer, the McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. (Some experts estimate this figure to be even higher.) Maggiori, who is white, understands that some might question whether a Black artist might have been a more appropriate choice for this honor, but he counters by pointing out the potential impact of the work. “Kids are going to go to this museum, and then go home and say, ‘There were Black cowboys, Dad.’”

Maggiori has also supported the Black Cowboy Museum in Rosenberg, which is a couple hours’ drive from the Briscoe. It’s founded by Larry Callies, who comes from a long line of cowboys, including uncles and cousins. When as a child he was told by other kids that there was no such thing as a Black cowboy, Callies’ passion for cowboy culture only grew. He became a country singer (modeling his style after Black country star Charley Pride and, for a time, sharing a manager with George Strait). After experiencing voice problems, he eventually began working on his museum, which opened in 2017. “I didn’t want what the cowboys did back in the 1800s to go in vain,” he says. “In Texas, it was hard to be a Black cowboy. People didn’t know about it.”

A similar experience helped shape Paul Stewart, who founded the Black American West Museum & Heritage Center in Denver, Colorado, which has been introducing visitors to authentic cowboy history since 1971. In non-COVID times, it hosts reenactments by Black cowboys, including board member Eleise Clark-Gunnells, and it’s also home to a treasure trove of artifacts from Black Westerners. The effect is often overwhelming on visitors of all backgrounds. “That’s what our museum offers, a jaw-drop moment,” Clark-Gunnells explains. “The only way to perpetuate racism and prejudice is to not tell their story.”

Telling that story came late to Thomas Blackshear, who experienced decades of success as a commercial illustrator for Hallmark and George Lucas, among others, before turning to Western art around 2016. “I was at the lowest point in my career,” he says now, citing struggles with a company he worked for on a line of figurines. Within a year, he had gallery representation, due to both his talent and a unique perspective on the West. “You just don’t see a lot of paintings of Black cowboys,” he says. “One thing I wanted to be sure about is that people don’t peg me, because I’m a Black artist, as someone who paints Black cowboys. I’m an artist, who happens to be Black, who can paint anything.”

As Western art continues to resonate with collectors young and old, Blackshear (whose painting was recently on the cover of The Killers’ album, Imploding the Mirage) sums up the appeal. “Let’s just go back—why do people in America love the West? I think it has a lot to do with that time, with the pioneer spirit, the types of people who were rugged self-made men. It’s that romantic feeling. Especially when it got to Hollywood, the legend and the romance of that way of life. That’s what people really relate to—and it’s a time that passed by.”

Artists like Blackshear are ensuring that, while the time may have passed by, its true legacy remains for generations to come.

- Images courtesy of Teal Coke Blake

- Images courtesy of Mark Maggiori

- Images courtesy of Logan Maxwell Hagege

- Images courtesy of Thomas Blackshear