The Mythmakers

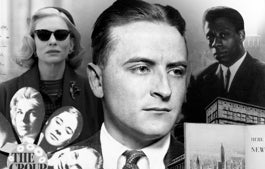

In the first installment of the RL Fiction Project, a young woman reflects on the cinematic glamour and mystery of a great love from long agoFor nearly five decades, Ralph Lauren has turned his creative visions into art, most famously in collaboration with photographer Bruce Weber. Mr. Lauren’s designs have been inspired by a combination of real life, fashion, scenes from classic movies and great literature and figments of his own boundless imagination. And throughout the photographer’s relationship with Mr. Lauren, Weber has displayed a knack for capturing those inspirations on film.

Welcome to the RL Fiction Project, in which we pair notable young writers with iconic Ralph Lauren advertising images, and watch what unfolds. For our first installment, we chose an unforgettable photo shot by Weber in 1987, one that encapsulates the Ralph Lauren look today as beautifully as it did back then. For our debut writer, we chose Stephanie LaCava, whose memoir, An Extraordinary Theory of Objects, as well as personal essays in Vogue and The Paris Review, have helped define the new young American voice. Using Weber’s picture as her prompt, LaCava created a world inspired by Weber’s image, which was inspired by Mr. Lauren's fashion, which was inspired by…well, you get the idea. Herewith, “The Mythmakers.”“You know, angel, how sea horses are made?”

My grandmother fancied herself a mythmaker in many ways. I wasn’t allowed to call her Grandma Wallis or Granny or Nana, always Grandmother.

Though he’d had similar tendencies, my grandfather was just Grandpa.

“Don’t know,” I said. It was the night before Christmas, and I was wearing a plaid dress with smocking on the bodice below a stiff white Peter Pan collar, legs curled up in her lap, tiny Mary Jane shoes hanging over the old leather armchair.

“A dragon fell in love with a shrimp,” she said, “and the rest was history.”

I decided then that the sea horse was my favorite animal (they were Grandmother’s, too) and that I was allergic to shrimp. And from that point forward, all animals were created by some kind of creature coupling.

Trying to get comfortable, I pulled off my shiny black slippers.

“Keep your shoes on, angel. We’re going to the movies.”

“Why?”

“Dinner needs to be set up, and we can’t get in the way. There’s a big party tonight.”

“Where?”

“Here,” she said, looking away to the corridor just beyond her door. We were sitting together in her dressing room in front of an enormous Art Deco mirror. I can still see it—three panes of glass like the silhouettes of enormous bell jars with tubes of lighting on either side. I’m not sure if I remember, as I sometimes do, simply because I’ve seen it in a photo or if I remember when I was actually there.

Grandmother was beautiful, often mistaken for a younger woman with her sculpted, whippet-thin body and dark brown hair. Her wardrobe was slim, specific. On weekends, she wore soft cream sweaters and black tailored pants. When she went out at night, it was always in a tight black dress that often dropped low to the small of her back. She said Grandpa loved her back, that he would stand next to her and place his hand at the curve where her dress ended and bare skin began. When I grew older, I realized that this must have been where he held her during their most intimate moments. She was so limited in her displays of affection. Until I came along, only he received her warmth in public. My mother and Grandmother had always been a complicated pair.

I stood behind Grandmother that night, hugging a leg as children do, staring upward, studying. She never cared for flashy things, never wore much jewelry and seemed dismayed at my mother when Mummy did. But on special occasions, she wore a pair of gold bangles my grandfather had made for her, one for each of her children, Mummy and her half brother. My uncle died in a riding accident when he was in his early 20s. The horse was called Odie. I remember my uncle whispering it over and over, quietly, with a kind of dark respect, “Oh-dee.”

Years later, I tried to replicate how Grandmother stepped into the back of the car, all grace even as I held tightly to the hem of her dress. I can see her in the frame of a photograph, a grainy 3-by-5-inch card with the date and time printed in square digits in the lower right corner. The picture looks like it is of an out-of-focus Christmas tree or traffic lights, but upon closer inspection, it’s of a gaudy movie-theater marquee. Grandmother had stopped in front of the cinema and taken a photograph of the signage with a tiny shutter camera that she kept in her purse. It was an extraordinary break in character, an attempt, I think, to capture something she had lost long before. My grandfather had made the film that played that night, years ago but some time after they first met.

If she was beautiful that Christmas Eve, she was unreal when she was young. It was said that no man could resist her, Grandpa included. She was married when she met him, to an older man, a poet and the father of my mother’s half brother.

Grandpa had claimed that when he first met my grandmother, he knew immediately that she was his great love and theirs would not be an easy love. They met at the very house in which she lived—where my mother grew up and where dinner would be served for us after the movie. She gave grand dinners there for her first husband and his friends—other poets, artists, people like that. Grandpa had attended that night because he’d promised a friend he would, although it wasn’t much his scene. He was quiet, reserved, sometimes strange around people, but Grandmother loved this about him. Theirs was a game of secret messages, minor scandal and finally great love.

Mummy was supposed to come with us to the cinema in the city, but she decided to stay at the house in the country. She and I visited Grandmother only once or twice a year. But Grandpa’s movie was being reprised at an old film-school theater in downtown New York, and Grandmother insisted on seeing it with me that night on the big screen.

So we went alone, me in my smocked dress and she in her black one with Grandpa’s fisherman’s sweater thrown over her shoulders. It was just long enough to cover where the dress dipped in the back. She wore it like a cape, and it slipped a little when she reached for my hand, which she held throughout the movie until the credits rolled.

“Look,” I said midway through the movie, “there are sea horses!” They were hard to see, swimming in a fish tank in the background of a dynamic scene.

She didn’t answer but nodded as if she’d noticed them a thousand times.

Years later, Mummy told me about some of the subtleties of Grandpa’s films. He had a thing for insects and horses—equestrian themes and motifs always appeared somewhere. Grandmother rode competitively until the birth of her first child, when she decided it might be too risky, which is ironic, considering what happened to my uncle. Grandpa believed, I am told, in the power of images and the play of light, in particular, reflection and shadow. It was typical of a movie man, but what surprises me is how he used those elements to charm my grandmother. She wasn’t an easy study.

“What was Grandpa like?” I once asked Mummy.

“He was a stoic, sad man,” she said. “He would have loved you. He used to tell me, ‘Tilly, your mother is fascinating. She’s like a science experiment.’”

“That is good?”

“Yes, very good. It meant she surprised him, even after being together for so many years. She always inspired him.”

“Means she was crazy, like your Mummy,” my father yelled from inside his study. Mummy laughed. “He’s joking, my love,” she said. “He means that in a nice way. You don’t ever want to be bored.”

I think my father had become bored.There didn’t seem to be anything boring about my grandmother or the stories surrounding her, though. She wasn’t just beautiful or well spoken or funny. Rather, it was the sum of all that, an allure and charm that blossomed when she felt at ease and her walls came down, even when she was acting, in my father’s phrasing, “crazy.” It’s hard to understand what could be so comforting about an icy beauty, but she understood Grandpa. She didn’t mind his strange affectations. Women often pretended to like him, but he knew the difference. She didn’t need anything. She had a lot to lose. Together, the two were magnetic, despite their best intentions.

When Grandpa met her, he was uncertain about the prospect of a woman who was already taken by a man so different from himself. Grandpa wasn’t always a filmmaker; back then, he worked on Wall Street, and a great deal of time would pass before he began to make movies. He’d always been insecure about his artistic leanings, believing them to be impractical and self-indulgent. Grandmother felt otherwise, and it was she who nudged him to work on his films full time, she who supported his new career.

After that first dinner, they met again at another. This time, she wore a black dress with a deep dip in the back and gold laurel leaves forming an X across her skin. On her wrist were those two bracelets. I remember it exactly, whether from a photo or a tale.

When she saw my Grandpa arrive, Grandmother left the dining room to collect herself. She slipped away to her dressing room, stood in front of a mirror and pretended to fix her hair. Grandpa followed her. They had made brief eye contact once before and then nothing more until that moment in the boudoir. She pretended not to see him, though he knew she had, and thus their game began. Grandpa played it quietly, aiming for the long target, the eventual win.

That night after the movies, Grandmother gave my mother a small silk pouch.

“Save this, Tilly,” she said.

“What is it, Mum?”

“Something for you one day, angel.” And Grandmother looked at me.

Not much time passed before Mummy gave me the pouch as ordered. Inside it were notes of modern courtly love. I didn’t know how to read them then, but I remember the stationery on which they were printed just as I remember all the photos and the film. Each was crafted from cream-colored heavy paper stock and at the top, engraved in navy script, was the monogram WMT. Below, limericks and doodles scribbled in Grandpa’s hand filled the page. He had hidden them all over her house that second night.

When I look through these cards now, I am reminded of that evening at the movies with Grandmother holding my hand. I remember being taken with the film, almost frightened by it, though I can’t remember much of the plot or what became part of the lore. It’s the same feeling I had that night when Mummy caught me looking in Grandmother’s jewelry box after we returned from the cinema. She had come to tell me dessert was being served. Before announcing her presence, she stood for a while in the doorway, watching. I caught her reflection in the vanity mirror, just as I imagine Grandpa saw my grandmother, and she caught me examining one of those gold bracelets, on which tiny creatures were engraved—sea horses—their tails curled and sharp noses upturned.

Since that evening, I have watched every one of my grandfather’s films, and in each, I try to find anachronisms—incongruous outfits or misplaced props. I find them in my memories, too. Grandmother could not have worn those bracelets on the night she and Grandpa began their affair, as he was the one who gave them to her years later. He was quiet, but through those movies, he told her how he saw the world, how he felt about her and about being with her in it. There was a sea horse hidden in nearly every scene. He told her half-truths and half-lies but always a good story—as all good mythmakers do.- © Vertis Communications

- PHOTO BY BRUCE WEBER, COURTESY OF RALPH LAUREN CORPORATION